While it is not feasible to save every building or structure, our mission at Preservation Utah is to save as many as possible, advocate for preservation in our state, and empower others to preserve Utah's built history and cultural treasures.

Below is a list of Utah's most endangered places. These structures are in danger of demolition or collapse due to neglect, development, natural disaster, or a combination thereof. We ask that people in the surrounding neighborhoods and communities where these structures are located make their voices heard to help save these historic buildings and places. Reach out to your local, state, and/or church leaders; form community groups; interact with the media in your area; and advocate to save your local history.

The list is not ranked; rather, the historic sites are listed in alphabetical order by county. Stay tuned for lists denoting the most endangered places in each county (including the ones below) to be released throughout the year.

Do you know of threatened buildings or spaces in Utah?

Cache County

Logan Main Street

Photo courtesy of Tracey Smith

Logan, Utah, was founded in 1859 and named after a fur trapper who had been an early white settler in the area. The town has had periods of growth after the construction of Utah State University, during the post-WWII Baby Boom, and again recently. Logan’s Main Street was the anchor for the town – the surrounding neighborhoods grew out of it and Center Street.

Unfortunately, despite a healthy growing community, several historic buildings from that Main Street core were recently demolished for the City of Logan’s downtown “revitalization” efforts. Two buildings from the 1890s – 47 and 67 Main Street – were torn down, along with the historic library built in 1916. Two more historic buildings at 41 and 45 Main Street remain in limbo for their future as the City moves forward with the construction of a new plaza. And that’s without pointing out that historic buildings elsewhere along the street are not in danger after the recent destruction of their neighbors. Revitalization is great, especially for struggling towns (which Logan is not), but those efforts should not exclude historic preservation. Adaptive reuse can provide new uses for old spaces, while preservation of historic structures keeps a beautiful aesthetic in historic Main Streets across America. Rather than dispose of their historic buildings, Logan should work to preserve and utilize their historic downtown core. Although there are no overt threats to Logan’s current vintage buildings, the city’s Historic Preservation Committee was ineffective in saving structures over one hundred years old in the heart of the Center Street National Historic District, which merits note as being an endangered district.

Join Preservation Utah Today to Save our Historic Built Environment

Salt Lake County

Abravanel Hall and Japantown

Abravanel Hall Photo Credit: Visit Salt Lake

The north side of 100 South housed many Japanese-owned businesses until it was demolished to make way for the Salt Palace in the mid-1960s. (Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah) KSL News Radio Article 3/20/24

Salt Lake City's downtown skyline is on the cusp of transformation, as plans for ambitious redevelopment projects between West Temple and 300 West promise to redefine the urban landscape. Amidst the excitement of revitalization, however, two beloved landmarks stand at a precarious juncture: Abravanel Hall and the historic Japantown district.

Abravanel Hall, named in honor of the conductor Maurice Abravanel, has been a cultural cornerstone since its establishment in 1979 as the home of the Utah Symphony. Renowned for its impeccable acoustics and stunning architecture, the hall has enchanted audiences with its performances. The exquisite interiors of Abravanel Hall, adorned with gold leaf-covered tiers and opulent details, speak to a commitment to excellence and a reverence for the arts. Yet, the hall now faces a dual threat: the broader redevelopment plans and proposed internal renovations. Its fate hangs in uncertainty, lacking protected status, sparking concerns about the county's commitment to preserving this iconic structure.

The proposed overhaul of the Salt Palace Convention Center, a part of the downtown redevelopment, raises further questions about Abravanel Hall's future. While the potential for enhanced connectivity and urban vibrancy is enticing, it underscores the need to safeguard cultural institutions like Abravanel Hall amidst rapid urban development.

In juxtaposition, Japantowntown had been a vibrant hub since the late 1800s, and it stands as a testament to the rich history and resilience of the Japanese American community in Salt Lake City. Nestled between Second and Third West on 100 South, this street has been a vibrant hub since the late 1800s. However, the proposed project threatens to erase what remains of this historic enclave (after it was already decimated by development in the 1960s), posing a significant risk to its cultural legacy. For advocates like Jani Iwamoto, Utah state senator and staunch supporter of Japantown, the fight to preserve this landmark is deeply personal.

As discussions unfold and decisions loom, the challenges facing Abravanel Hall and Japantown underscore the complexities of urban redevelopment. Balancing progress with the preservation of culture and identity is paramount. The absence of protected status for Abravanel Hall amplifies concerns about its vulnerability, prompting stakeholders to advocate fervently for its preservation.

Both Abravanel Hall and Japantown represent more than just structures; they embody Salt Lake City's collective memory. Their fate is intertwined with the city's identity and the stories of those who have called them home. As the city navigates its path forward, it must heed the lessons of history and recognize thevalue of preserving its cultural heritage for future generations.

West High School

Photo courtesy of Preservation Utah Staff

West High School is the product of more than a century of public ambition, effort, and investment. As we consider this building’s future, we should also remember its past. Specifically, we should fully understand what it took to build and then sustain this remarkable building for 101 years. It was built before the I-15 corridor reinforced the east/west divide in Salt Lake City. It was built before large swaths of the city’s west side were redeveloped with convention centers, malls, parking lots, and infrastructure expansions. Once home to a diverse community at the intersections of Greek Town, Japan Town, and the Marmalade – it has continued to serve both the west, east and north sections of our city – one of the very few buildings to truly promote integration and foster a single community experience. We recognize that this building embodies a century of excellence in education, school spirit, and community pride. It is a prime example of 20th-century craftsmanship and iconic school architecture. For over 100 years, it has helped build and tie together Salt Lake City’s west side, downtown, Avenues, Granary, and Marmalade districts.

In February 2023, the architecture firm tasked with the school’s renovation proposed four options, only one of which fully preserves the school. However, preservation is not only possible but also feasible. Ogden High School stands as a prominent example of preserving the original building and continuing to use it as a school. South High School (now part of Salt Lake Community College) and Park City High School (now the Park City Library) stand as two prominent examples of adaptive reuse. After the completion of the first phase, the district contracted with the surveying firm Y2 Analytics. In Spring 2024, they will conduct focus groups, surveys, meetings, etc.

In 1921, local newspapers described West High’s design as reflecting the then-popular “school Gothic” style, intended to recall elite educational campuses on the East Coast of the United States and the United Kingdom. When the school’s construction ended in the fall of 1922, many commemorated the vision reflected in the new West High School. School and district leaders were heralded for their vision, others credited the skill of architects and builders, and politicians were credited with making West High School a reality. The remaining façade, terracotta ornamentation, vestibuled entries, school clock, formal landscaping, and site placement are largely original and strongly contribute to the school’s continued architectural value in the city.

We recognize that the school is nearing or past its prime as an educational facility and needs to be updated. However, we believe that it is not primarily the historic main block that drives this need but rather the need to upgrade or add advanced STEM, Arts, and Music teaching facilities. We believe these facilities can be added to the campus without demolishing the historic structure's key elements.

Fifth Ward Meetinghouse

|

|

|

Photos courtesy of Preservation Utah Staff

The Fifth Ward Meetinghouse in Salt Lake City, a cornerstone of the local community, stands as a testament to over a century of history and evolution. Built in 1910 and designed by architects Cannon & Fetzer, and remodeled in 1937, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978. There was even a historical marker on the building. It is also an official Salt Lake City Landmark site. This red-brick structure served multiple purposes throughout its storied existence, reflecting the changing needs and demographics of the surrounding area.

Originally constructed as an LDS chapel, the building underwent numerous transformations over the years, adapting to accommodate various uses. At different points, it served as a photo studio, music venue, office space, and even housed goth/industrial nightclubs. In 2004, it found new life as a Tibetan Buddhist temple, known as Urgyen Samten Ling Gonpa, following extensive restoration efforts by dedicated volunteers. Despite its rich history and architectural significance, the building faced neglect in its later years, with boarded-up windows and signs of disrepair evident to passersby.

The recent unauthorized partial demolition of part of the historic assembly hall has sparked outrage and concern among residents, highlighting the precarious balance between development and preservation in Salt Lake City. It serves as a poignant reminder of the city's rapidly changing landscape and the need to protect its architectural heritage for future generations.

As the city addresses this egregious violation, efforts have been made to ensure that no further damage is done to the site without proper permits and inspections. Community leaders and Preservation Utah are committed to safeguarding the remaining structure of the Fifth Ward Meetinghouse and taking proper measures to prevent further unauthorized alterations.

LDS Wells Ward

Historic Photo Courtesy of Marriott Digital Library

The LDS Church is in the process of selling this building and plans to raze it because of 2020 earthquake damage. According to LDS Preservation Officer Emily Utt, the building has been condemned, and after 18 months of analysis by engineers, architects, and historians, the LDS Church decided not to restore the building because workers would have to demolish ¾ of the building and rebuild it at an estimated cost of $5 million. Besides structural damage, the interior and exterior of the building have been vandalized.

But the building is worth saving. Its classrooms and amusement hall were built in 1920, and the chapel addition was built in 1926 in a muted neo-Jacobean style, an unusual architectural style in the U.S. and in England. The building sits on just over 1 acre at 1990 South 500 East, Salt Lake, and for over 100 years has served as a community space and place of worship for Liberty Wells residents. The chapel has sponsored blood drives, Friday movie nights, carnivals, festivals, square dancing, dinners, road shows, and literacy projects. It was built at a time when local neighborhoods raised funds for the construction of wards themselves (in this case, $45,000). The land was donated by Daniel H Wells, an early LDS Church leader.

After the Church announced that they would not restore the building, in November 2021, LDS Stake President Nat Carson presided over a “Wells Building Farewell Commemoration” in which he expressed regret at losing the building and said he never wanted to be present for that day. At the end of the program, the congregation had the opportunity to take souvenirs from the building. In March 2024, the Liberty Wells Community Council, quoted in the SL Tribune, acknowledged the imminent sale of the building and said they would like to see missing middle housing development on the one-acre site because of the “critical housing shortage” in Salt Lake. On the other hand, City Council Member Darin Mano, District 5, says, “there is definitely neighborhood support for preserving the chapel.”

Its unique style, combined with the structure's importance to the community and to the LDS faith, make it a priority to preserve.

Historic Districts in Salt Lake City

|

|

Photos courtesy of Jack Davis

Buildings that contribute to the historic built environment within the National Register and local districts are considered worthy of preservation and may qualify for incentives and grants to support their long-term survival and integrity. Local historic districts in Salt Lake City may further offer some protection from demolition for buildings that contribute to the fabric of these historic neighborhoods. Many of Salt Lake City’s historic neighborhoods are included in local and national register-designated historic districts.

However, the rapid pace of urban development poses significant threats to these cherished districts. Significant development pressure resulting in increasing land values and changing land use policies has resulted in the demolition of many contributing historic structures in Salt Lake’s historic neighborhoods, including several recently. For example, despite being a local historic district offering certain protections from demolition, Salt Lake City has still allowed the demolition of 51 contributing historic structures in the Central City historic district since its adoption in 1991.

Additionally, Salt Lake City has recently adopted an ordinance that allows its planning department to administratively change the contributing status of historic buildings and remove their demolition protections with very limited public process. Allowing for administrative changes to the contributing status of buildings does not afford the preservation community and other experts the opportunity to evaluate and comment on whether such changes are merited and appropriate under applicable preservation standards.

The delicate balance between preserving the past and accommodating future growth is in jeopardy, as demolition and insensitive alterations loom over the beautiful historic buildings that define Salt Lake City's essence. Without concerted efforts to safeguard these districts, the City risks losing invaluable pieces of its identity and eroding the sense of community that has flourished for generations.

Join Preservation Utah Today to Save our Historic Built Environment

Salt Lake City’s West Side

|

Georgian Influenced Single Cell House |

569 W 400 N |

Admin Building |

Citizen Coal |

|

Hepworth House |

McKean House |

Wheeler Whipple |

Photos courtesy of Michelle Watts of Fairpark Neighborhood

Salt Lake City’s “West Side” includes Rose Park, Fairgrounds, Ballpark, Glendale, Westpoint, and Poplar Grove neighborhoods. While Salt Lake City’s historic West Side presently resides between about 200 W or 300 West and I-15, collectively, “West Side” references anything within Salt Lake City's bounds that is west of I-15. These neighborhoods offer a range of historical contexts from early, Native American history and culture; post-World War I and post-World War II architecture; pioneer-era homes; B.I.P.O.C. and Queer history; and a variety of original styles like Victorian, craftsman, California bungalows, Queen Anne, and California ranch homes. Each neighborhood has worked over the decades to gather and identify local businesses, structures, flora, and fauna. For example, residents of the Fairpark neighborhood pride themselves on living in proximity to the beloved historical fairgrounds and know how to navigate its many events and traffic. Additionally, numerous notable residents - and their historic homes - remain. Rose Park residents have, since their post-WWII beginnings, created a tight-knit sense of community and gathering amongst the former starter homes. “The west side has faced a long history of political, racial, and economic marginalization. Since the late 19th century, west side residents worked in low-wage jobs and took the brunt of industrialization while being the last to receive public health and infrastructure upgrades.” What makes West Side communities and neighborhoods remarkable is the community building and activism that has come to exist despite the consistent lack of resources, funding, protections, and help from the city and state.

Initially - as part of a “progressive,” nationwide cleanup movement - Salt Lake City began building its parks and infrastructure in the 1890s and into the 1920s at the expense of B.I.P.O.C. communities. Here, People of Color, prostitutes, and immigrants were forcibly relocated to the initial “West Side” of the City - today’s Granary District and around Pioneer Park - in stockades. These stockades were areas of housing and infrastructure created to hold and house these communities out and away from the downtown core and east side. Throughout the 20th century, poor, low-income, homeless, and People of Color continued to develop communities in the only place they were technically allowed to live in. Today’s neighborhoods and communities of the West Side flourished as a result.

In addition to “... some parts of the West side … originally [having been] designed … for manufacturing and [being] considered industrial zones instead of neighborhoods,” West Side neighborhoods deal with higher pollution rates than other Salt Lake City neighborhoods, higher crime and displacement, less hospitals and grocery stores, and less city beautification and investment. The older the West Side neighborhood, the truer this is, Fairpark and Glendale being older than the post-WWII community of Rose Park. With so many West Side neighborhood stories revolving around displacement and resilience, industrialization and discrimination, and nascent gentrification, much still remains to be done to correct these past wrongs. The histories of these neighborhoods and their residents are deserving of much more advocacy and cultural support.

Development, redevelopment, countless investments, and political campaigns have taken place to boost most neighborhoods east of 300 West or even I-15. However, Salt Lake City’s present West Side continues facing dire threats from aging homes and infrastructure, severely impacting community health and well-being. Many have seen contemporary development and protection at odds with preserving historical spaces and buildings. In truth, historical advocacy and preservation efforts can revitalize West Side neighborhoods to their former glory and accommodate the growing city’s modern needs. There is a severe lack of resources and investments to maintain the area’s historicity. This area contains a multitude of structures, lots, and stories from all chapters of Utah’s history. But they lack any kind of historical or cultural support and protection at any level.

Today, Preservation Utah views Salt Lake City’s West Side neighborhoods as being in dire need of historical protections and will begin to lead efforts to change this. Each West Side neighborhood is deserving, in its own rights, of local recognition and protection as unique individual historic districts. Today’s residents deserve the resources that would additionally come with these recognitions and cemented protections. Past residents deserve the recognition and honor associated with having their stories and spaces preserved. While redevelopment has not reached West Side neighborhoods as we see in downtown and central neighborhoods, the threat is imminent. West Side neighborhoods can accommodate more families and affordable housing while maintaining their own historicity and significance through local, state, and federal protections and recognition.

Our Lady of Lourdes

|

Photo courtesy of Steve Cornell |

Photo courtesy of Preservation Utah staff |

Standing on the southeast corner of the Judge Memorial School block, with a commanding view of Salt Lake City below it, Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church has continuously served the city and the Catholic community for the past 110 years.

As the catholic diocese is planning the relocation of Judge Memorial High School and the sale of the property on which it sits, the historic church is being threatened with demolition. Please help us save this sacred building and important landmark of Salt Lake City's history.

At the time of the Church’s construction, the land now occupied by Judge Memorial Catholic High School was the site of Judge Memorial Miners’ Home and Hospital (Judge Mercy Hospital). Mrs. Mary Judge, the widow of miner John Judge, made a sizable donation to the Diocese in 1900 for the construction of this institution, which opened in 1910 to provide care for infirm and retired miners and miners who needed medical treatment often associated with black lung disease. The hospital was underutilized and closed in 1915, but in 1918, Bishop Scanlon of the Catholic Diocese turned the operation of the hospital over to the Red Cross, who used it to serve influenza (Spanish Flu Pandemic) patients from throughout the valley. In 1922, the hospital became Judge Memorial Catholic School.

Over the next 100 years, the small church next door, Our Lady of Lourdes Church, welcomed, promoted, and supported Catholic education from Kindergarten through Grade 12. Ultimately, in the mid-20th century, the parish built Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Elementary School next to the church, staffed by Sisters of the Holy Cross. Judge Memorial became a high school for grades 9 through 12.

Lourdes Church has been and continues to be the spiritual home of a dynamic, welcoming faith community. In addition to the celebration of daily Mass, 5 Masses are celebrated on weekends: 3 in English, 1 in Korean, and 1 in Filipino/1 Spanish on a rotating basis. Several movies were filmed in the Church, including Stephen King’s The Stand. During the World War, the parish bought war bonds with building funds in anticipation of their post-war 1951 remodel.

Presently, the Diocese of Salt Lake City is exploring the possibility of selling the property on which Judge Memorial and Our Lady of Lourdes Church are located. The parishioners of Our Lady of Lourdes Church, many neighbors, community partners, and alumni of Judge Memorial would like to keep their historic church. The Church is home to a vibrant, ethnically diverse, and charitable community, which is financially solvent and in great condition. It is important to note that despite its rich history, unique architecture, and listing on the National Register of Historic Places, the church itself is under no historical protection.

San Juan County

Oljato Trading Post

|

Photo courtesy Will Pratt |

Photo courtesy Steve Cornell |

Photo courtesy Steve Cornell |

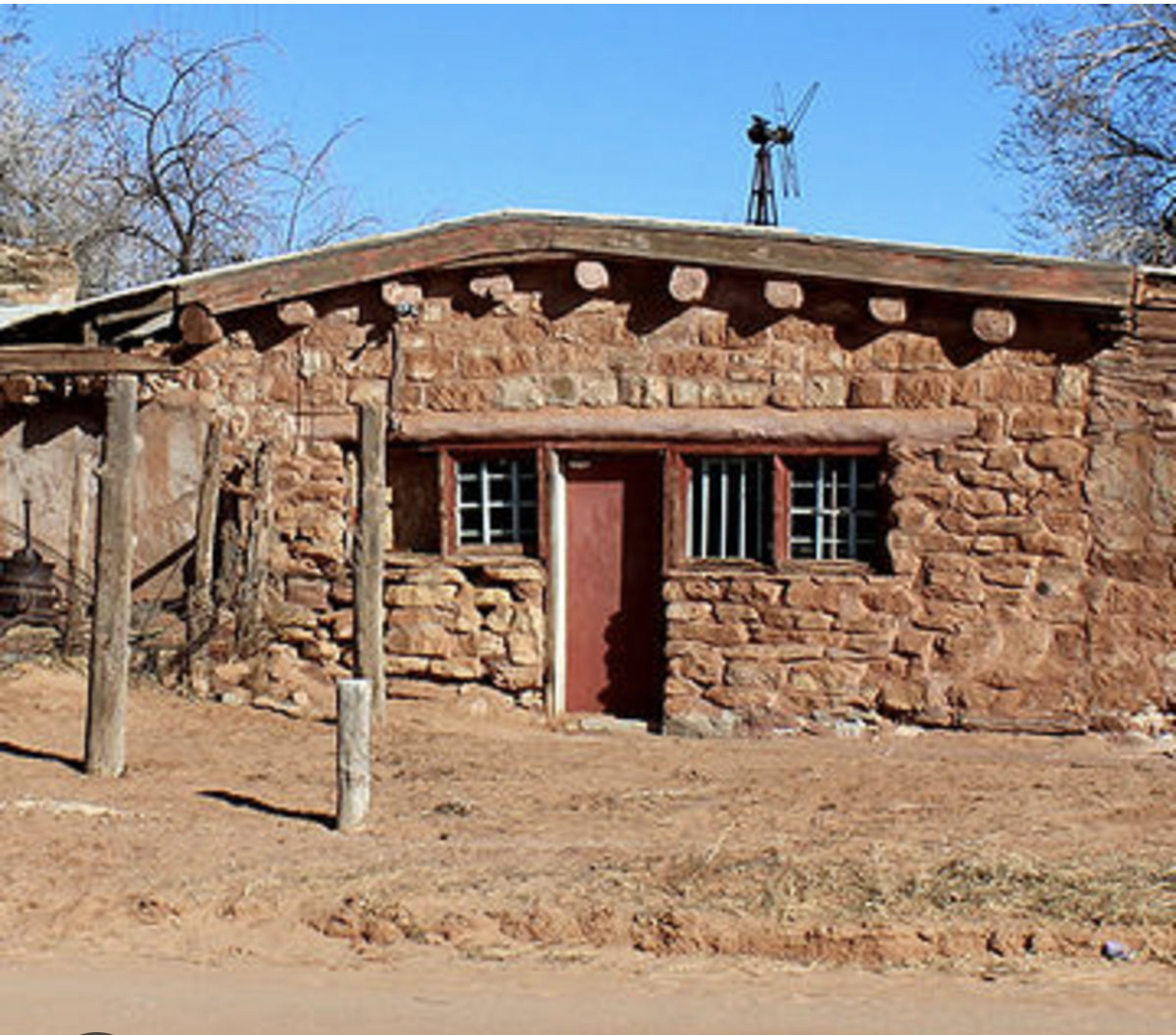

Oljato Trading Post was a trading post located on the western edge of Oljato-Monument Valley, Utah, south of the town of Bluff. The name comes from the Navajo word ‘Oljee’to’, meaning moonwater. Founded in 1906 by John and Louisa Wetherill, the trading post is located in one of the most isolated places in the US. The Wetherill’s brought in supplies by horse-drawn wagon from Gallup, New Mexico, a 21-day trip! The present-day structure was constructed in 1921 by a licensed Anglo trader, Joseph Hefferman.

In the following years, the trading post had several owners. The post included designated areas for trading wool and lambs, loading areas for wagons, storage, and an elevated area for overseeing the trading area. The trading post was once a lively economic and social hub. Navajo Nation citizens gathered there to buy and sell goods such as woven baskets and wool rugs, place telephone calls, or simply mingle with one another.

The 1921 Oljato Trading Post was added to the National Register of Historic Places on June 20, 1980. It closed in 2009 and slowly fell into disrepair. By 2019, the structure had deteriorated further, and the San Juan County Historical Commission had engaged the Utah State Historic Preservation Office, hoping to save the structure. The office helped establish partnerships with the Navajo Nation, Preservation Utah, and government agencies to complete a historic structure report to identify critical preservation needs. With some limited grant funding and donations, some work was completed in 2020 to help stabilize the structure, clean up the site, and conduct roof repairs.

In 2021, the National Trust for Historic Preservation named Oljato Trading Post one of America’s Most Endangered Places. Further work must be done to preserve the building, and advocates continue raising money for future restoration work. The post has significant historical and cultural value and deserves to be preserved for future generations.

Join Preservation Utah Today to Save our Historic Built Environment

Summit County

A-Frames

|

Photo courtesy Dalton Gackle |

Photo courtesy Dalton Gackle |

Park City has lost over 70 structures built from 1963 through 1975 in the last twenty years. That’s from a starting point of approximately 185 structures within Park City limits, not including condominium complexes. This means Park City has already lost approximately 38% of its Ski Era buildings.

The Park City Planning Department has recently received numerous inquiries on the historic status of homes in the Ski Era in order to determine demolition eligibility. A-frame homes, especially, have nearly disappeared from Park City. Only two true A-frames, where the roof is a full triangle all the way to ground level, remain. A third traditional A-frame was expanded onto, leaving the original design obscured. Another 17, which are still just as relevant, are all modified-roof, gambrel-roof, or gothic-arched (pregnant) A-frames.

There is at least one demolition currently pending in Park City for an A-frame. Regular continued development and a potential for extreme development with the likelihood of another Olympic Games in Park City further put structures of this era in jeopardy if they are not protected.

Many Parkites and Summit County residents, especially homeowners and previous Park City government administrations, do not view or have not viewed Ski Era structures as historic. Many reasons for this include long-time and former residents’ living memory and “modern” styles, which many view as un-historic. But in terms of longevity, local, regional, and national cultural and historical significance; and architectural style, these structures are historic and should be treated with the same respect as Park City’s most notable mining structures and Mining Era homes.

The Park City Museum is including ski-era structures in its historic building and preservation ribbon awards. Still, there are no plans from the City for ski-era homes, individually or collectively, to be added to Park City’s Historic Sites Inventory, which comes with demolition protections.

Several similar towns to Park City and other entities have added recognition of significance, historic preservation requirements, and demolition protections to homes in the range listed, including Aspen, Colorado; Boulder, Colorado; and Scottsdale, Arizona.

Byron T. Mitchell Home

|

Photo courtesy Dalton Gackle |

Photo courtesy Dalton Gackle |

Byron Teancum Mitchell married Emmeline Janett Andersen in 1895. They first lived with Byron’s mother in Kamas, but in 1897, after the birth of their first child, Byron began building a new home in Francis, now at 2198 South State Road 32. Byron’s brother ran a brick kiln in City Canyon, so the house was one of the first brick homes in the area. Byron designed the house himself and is a good example of local vernacular eclecticism. It is a combination of a cross-wing plan with Gothic Revival, Second Empire, and Victorian styles.

Unfortunately, while the home is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, it has sat vacant since the 1970s and is in danger of demolition by neglect. On top of that, an out-of-state developer has bought the property. Francis does not have any historic districts or demolition protections for historic buildings, meaning the home is currently at the will of the developer. Rising property values in all of Summit County have this home in a precarious position, in addition to its already deteriorated state.

Thaynes Headframe Building, Silver King Headframe Building, and Silver King Mill

|

Photo courtesy Dalton Gackle |

Photo courtesy Dalton Gackle |

Last winter, the roof on a significant portion of the Thaynes headframe building collapsed due to heavy snowfall, likely damaging interior structures and equipment as well.

The Thaynes headframe building—completed in 1937—and shaft—completed in 1939—were constructed by the Silver King Coalition Mines Company to connect with the company’s Spiro Tunnel.

From 1965 to 1969, it served, along with the tunnel, as the world’s only underground ski lift. Skiers got in line at the Spiro Tunnel portal, rode a train car through the tunnel to the Thaynes shaft station, then rode the elevator cage to the Thaynes headframe and exited out of its garage door. So, the structure tells portions of Park City’s mining and skiing histories.

The Park City Museum’s Friends of Ski Mountain Mining History (FOSMMH) has been working to save the remaining historic mine structures in Park City. They had plans to begin stabilization work on the Thaynes headframe and shaft this summer, with work continuing for several years. The recent collapse only emphasizes the work needed to retain what remains of this important structure, along with the more prominent and historically important Silver King headframe building over the ridge.

FOSMMH has already worked to stabilize and cap the shaft underneath the headframe at the Silver King Headframe Building. However, hundreds of thousands of dollars in stabilization, restoration, and repair work still looms to preserve the full building that encompasses the headframe, which they hope to accomplish over the next several years.

The Silver King Mining Company was formed in 1892 to manage the incorporation of several mines and additional claims in the area, including the Silver King, Woodside, Northland, and (original) Mayflower Mines. The massive headframe and mill buildings (plus several other attached or detached structures) were built at the site of the Silver King Mine, where the company controlled the processing and handling of ore from its holdings. The Silver King Mining Company (later renamed the Silver King Coalition Mines Company after it merged with another large mining company) was one of the world's largest silver, lead, and zinc producers through World War 2.

The FOSMMH has a capital campaign going to raise funds to stabilize and rehabilitate the two headframe buildings. Donations to help complete the work can be made here.

Lastly, the Silver King Mill, rebuilt in 1922 after a fire destroyed the original wooden structure and sitting a few hundred yards from the Silver King Headframe Building, is deteriorating at an untenable pace. The FOSMMH is focusing on the headframe structures, as they are more visible (at least in winter) to recreators. The mill building will likely also require a capital campaign to salvage and restore what remains of what is likely the largest standing historic mining structure in the United States. Still, that campaign is currently five or more years away.

Washington County

Administration Building

|

Photo courtesy of Rick Atkin |

Photo courtesy of Rick Atkin |

The county’s second courthouse, the erstwhile administration building, is located at 197 E. Tabernacle in St. George. An example of modern style architecture is the structure, which was designed by John S. Rowley in 1966 and is made of two stories of fieldstone, concrete, and glass. It replaced the Pioneer Courthouse, which still stands on St. George Boulevard. During the 1960s, St. George stepped out of its pioneer era into a modern era. This building holds historic significance as the symbol and cornerstone of the development and growth during the 20th century. A pillar of downtown’s government presence, the 28,000-square-foot building stands as one of Utah’s best examples of modern architecture with its clean lines and geometric shapes. Mid-century modern design is now more rare in Washington County, yet it has become more revered as time has passed. At various points, it housed the District Judge, County Clerk, Sheriff’s office, and the Justice of the Peace, the site of pivotal historic decisions in county chronology. Over a year ago, the new administration building opened to the west of this nearly sixty-year-old structure. The edifice is now at risk of demolition as Washington County plans to take the building down within five years.

Pioneer Courthouse

Photo courtesy of Will Pratt

The Old Washington County Courthouse was the main courthouse for Washington County from its completion in 1876 until 1960. It is a two-story red brick structure with unusually thick walls (18 inches thick!). Situated prominently on St. George Boulevard, the structure rests on a basalt rock foundation that comprises the ground floor and is capped by a pyramidal-hipped roof with a prominent wood cupola. The cupola was designed for public hangings, but none were recorded as having occurred there.

The first floor served as offices for county government. The large room on the second floor was used as both a courtroom and a school room, as well as public meetings, plays, dances and a multitude of other activities. There is a jail with three cells in the basement.

After the courthouse activities were moved to a larger building in 1960, Washington County sought to tear down the old courthouse in 1970. St. George City decided to save the building and purchased it from the County that same year. The building was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on September 22, 1970. A major renovation occurred in 1986, and the St. George Chamber of Commerce occupied the building for the next 30 years.

The building has been unoccupied in recent years, although tours were given until very recently by the Washington County Historical Society, the current manager of the building. The sandstone used for the foundation of the building has slowly been eroding over the decades, and more extensive preservation efforts are needed to preserve the building for future generations.